Despatches from the Archives: A minor dispute & its imperial meanings – Tahiti, 1865

Despatches from the Archives is an occasional series in which I bring you interesting snippets of what I find during my research in the archives. The main focus of my work is the British Empire and its methods of rule, anticolonial resistance, and the cultural impacts of empire.

I recently spent some time in the archives doing a little preparatory work for a future book, looking at the Foreign Office records on the British Empire in the Pacific Ocean during the nineteenth century. This is not my usual region of study, so it has been refreshing to get to grips with a new part of the world, especially one as beautifully scenic as the Pacific.

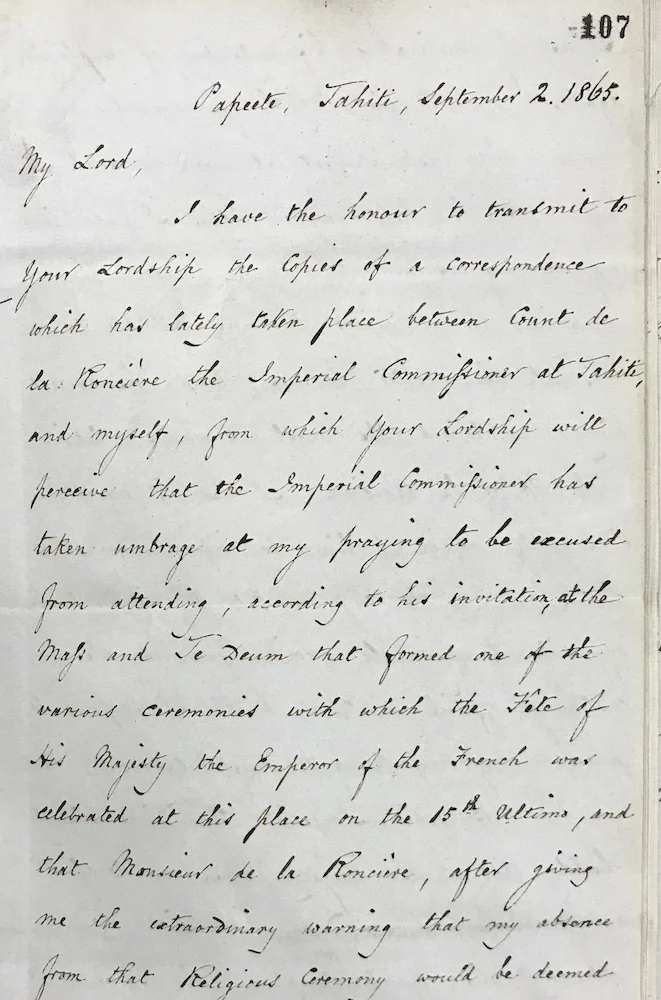

Consul Miller’s letter in the FO files

Some things, of course, don’t change along with geography, and even in the tropical splendour of Polynesia, it turns out that human beings will find petty things to argue about… When looking at the files for the French colony of Tahiti, I was amused to find some fraught correspondence detailing one such trivial diplomatic dispute from 1865. This little spat is almost comical in its stunning lack of importance, but it is also notably revealing about relations between the great powers of this era. As I wrote in my archive notes: “This is a very minor dispute of incredible silliness BUT it might be very usefully illustrative of the climate of Anglo-French rivalry in the region…”

The quarrel is detailed in correspondence from G. C. Miller, British Consul to Tahiti, to Lord Russell, the Foreign Secretary, dated September 2nd 1865 (see picture). With evident hurt feelings, Consul Miller begins:

My Lord,

I have the honour to transmit to your Lordship the copies of a correspondence which has lately taken place between Count de la Roncière the Imperial Commissioner at Tahiti, and myself, from which your Lordship will perceive that the Imperial Commissioner has taken umbrage at my praying to be excused from attending, according to his invitation, at the Mass and Te Deum that formed one of the various ceremonies with which the Fête of His Majesty the Emperor of the French was celebrated at this place on the 15th Ultimo, and that Monsieur de la Roncière, after giving me the extraordinary warning that my absence from that Religious Ceremony would be deemed to indicate something hostile to the Sovereign he represents, concludes his letter of the 14th of August by intimating his intentions of complaining against me to the French Government.

My astonishment at receiving such a reply to the polite request that I made in my note of August 12th, to be excused from attending the Religious Ceremony alluded to, was all the greater because, besides having all along maintained the most courteous relations with M. de la Roncière, I had in my above cited note begged of him to inform me at what hour on the Emperor’s Fête day it would be agreeable to him to receive from me the customary official visit at which I proposed to present my respects and congratulations.

G. C. Miller to Lord Russell, September 2nd, 1865

Hurt feelings and matters of prestige

Miller’s despatch runs to fourteen pages, and he also includes fourteen pages of copies of his correspondence with de la Roncière; the Foreign Office thus receives minute detail of what is in fact a trivial rumpus, surely suggesting some great feeling on Miller’s part. Amongst many other points, he raises two salient facts. Firstly, he is himself a Protestant, and therefore not entirely in the right place at a Catholic church service. Secondly, and importantly, for the preceding eleven years of his service as consul in Tahiti, he has not typically been expected to attend this annual event, doing so only on three occasions.

In addition, Miller reports that it has subsequently emerged that de la Roncière had intended on placing him (and the other consuls) in less prominent seating than would ordinarily be expected due to his rank, which Miller views as a significant slight. As he makes clear, he is greatly concerned about matters of prestige:

I cannot, My Lord, for a moment believe that I am bound, as Her Majesty’s Consul, whenever the local authorities may see fit to invite me to attend a Mass and Te Deum, to obey their invitation under pain, as in the present instance, of being deemed hostile to the state; because such a position would be obviously incompatible with religious liberty, and on the other hand could hardly fail to involve me eventually in serious embarrassments, besides bringing humiliation upon me in my public capacity.

G. C. Miller to Lord Russell, September 2nd, 1865

Lord Russell, 1861

Human foibles and hierarchy

That the official representatives of two hugely powerful empires should be preoccupied with such a minor matter is a sobering thought. It reminds us that even high imperial officials were only human, and possessed of human foibles and failings. When analysing historical events or interpreting the actions of historical figures, we should therefore remember this point. High office does not bestow omniscience, and not every act is strategic, or even properly considered; even decisions of state may on occasion be made out of spite or through some personal emotional response.

This affair also makes it clear that, when it comes to questions of official prestige, there are in fact no minor matters. Anything that could cause a loss of reputation, however small, becomes crucially important. Something that an objective and sensible outsider might regard as having no importance – seating arrangements at a church service to honour the monarch of another country, for example – assumes a magnified significance. For powerful empires and the ambitious officials who staffed them, position in the hierarchy was everything.

On a more human level, this text also demonstrates something of a universal truth: in any situation, if your counterparty insists on being petty, it is hard to avoid ending up also being petty. It is not always possible to maintain the moral high ground and walk away, especially for a government official. Even if you thought your opposite number was being silly, you still had to play the game…

Great Power rivalry but free trade in operation

Miller’s despatch also touches on some revealing issues concerning the way in which Britain and France regarded each other in the Pacific arena:

The trifling success that has hitherto followed the varied attempts to bring about the cultivation of Tahiti which have of late years formed the favourite pursuit of the French authorities, would seem to have revived the old impression that some counter-acting British influence must be at work, thwarting the present endeavours of the French, as during many former years was supposed to be the case in regard to their efforts for acquiring political supremacy over the Tahitian nation…

These prejudices of the French in Tahiti are the more singular and contradictory, since the principal agricultural and commercial undertakings in the country are carried forward by British subjects and British capital.

G. C. Miller to Lord Russell, September 2nd, 1865

This clearly shows the general atmosphere of rivalry and suspicion between great powers – indeed, even a touch of paranoia. At the same time, however, it also demonstrates a remarkable fact about the operation of free trade in the empires of the nineteenth century: the economy of a French colony could be dominated by British trading interests. The British subjects to whom Miller refers were, principally, two fascinating characters named Alexander Salmon (a Jewish Englishman, son of a Piccadilly greengrocer) and John Brander (the illegitimate son of a Scottish landowner).

A nineteenth century British map of Tahiti

Salmon and Brander found their separate ways to Tahiti as young men, established their own successful trading houses, and both married into the Tahitian royal family. The House of Brander became the largest trading operation in the South Pacific, and the Brander and Salmon families became dominant players in Tahitian business and society for several decades. Crucially, however, this did not challenge the French position as imperial masters of Tahiti (as part of French Polynesia), which demonstrates the possibility of separating business and rule, at least in the free-trading middle years of the nineteenth century.

Vexations: “…the position of the British consul is… generally delicate…”

Clearly, however, Miller felt that French perceptions of this situation made his own position somewhat fragile. He did not hold back in expressing himself to Lord Russell:

But the consequence is, my Lord, that the position of the British consul is, and all along has been, generally delicate, often difficult… things appear to have now reached a point when I can no longer in justice to myself conceal from your Lordship the susceptibilities and prejudices with which I have to contend, and which at times bring upon me vexations and even affronts.

G. C. Miller to Lord Russell, September 2nd, 1865

By diplomatic standards, this is robust language and we can feel Miller’s irritation through his carefully chosen words. That he should be responding so emotionally to what is, on the face of it, such a small matter certainly suggests a high degree of tension in relations between the two countries. This likely expresses rather more about the competition for power and influence in the Pacific Ocean than it does about attendance at church… In this way, therefore, even a “minor dispute of incredible silliness” can reveal something about the workings of nineteenth century empires.

The document quoted here is from the Foreign Office Records held in the National Archives in Kew, London: FO 58/104 – Pacific Islands, Consuls at Tahiti etc, Jan-Dec 1865